On Reagan Library

Created: 2023-04-01 (12:00:00) — Modified: 2026-01-28 (10:58:00)Status: completed

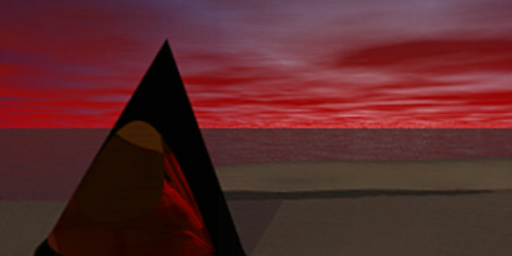

For a work composed of text and image, “Reagan Library” by Stuart Moulthrop fell into obsolescence, fast. A cybertext, it starts out promisingly enough if you enter it through the Electronic Literature Collection portal. Next to a screenshot of a fogbound coastline, the blurb describes the library as a “meditation on forgetting and loss in which text and image work together in an intricate and compelling way.” Its author thinks of it as a “space probe” but has no idea what you will think.

When you click into the library, though the text loads, the only image you will likely see is a grey box telling you it found no supported video format. Actually, looking closer, the text does not make much sense either:

What’s not to see? Check off each item as we don’t come to it: No dungeon, no gibbet, no infernal engine, no devil tower, no twisty little passages rife with hard targets… But… More than anything… Catachresis five… Not those fragments, these fragments… And another thing… Inspector 404…

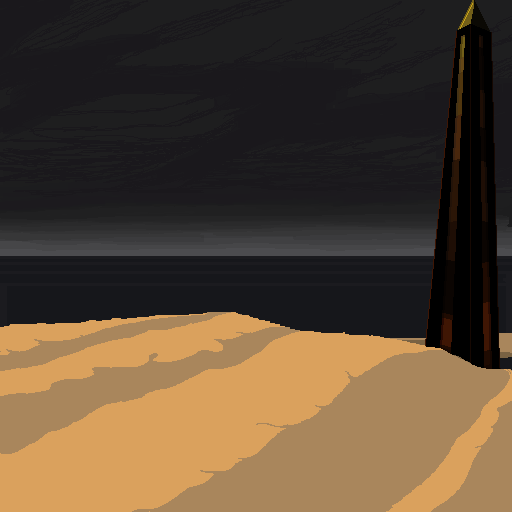

Follow one of the links and you will come to more text, another broken image. The sidebar at the last location was grey and told us we were at the pavilion. Here it is blue and tells us we are at the obelisk. The text:

On the morning after my thirtieth birthday, I took a backhoe to the vacant lot in Sarasota.

One graviton and falling…

Let us demonstrate. Ceaselessly improving the void. This is not a game. I remember this.

In my dragonfly eye, though, it was something much simpler.

Follow the only link available into another disintegrating text fragment, another grey box. And to another, and another, and another. Only, as you follow these links through the library, you will eventually begin to loop, to come back to the places you have already visited, and as you do, they slowly cohere. Back at the obelisk in the blue world after a couple loops:

On the morning after my thirtieth birthday, I took a backhoe to the vacant lot in Sarasota, gouged out a fair-sized hole, poured a few yards of concrete, and buried a time capsule in the red earth.

In my dragonfly eye, though, it was always something much simpler, something black, monolithic.

Following these links moves you between locations with names like the obelisk, the pavilion, the white cone, and between different narrative perspectives, points in time, even worlds. With enough loops the texts eventually return to their original forms.

But the texts are only one part of the library. They were originally accompanied by navigable panoramas–those grey boxes which now only read out an error–that looked like something out of Myst. That enigmatic screenshot in the introduction, the examples in this essay. They were implemented in QuickTime VR, a long-defunct video format, and the only way to view them now is through a separate program. I used one called Videopanoramas Player

If you go to the trouble of downloading and viewing each panorama, the shape of this library suddenly becomes clear. All of these text fragments are located within, and obliquely referring to an archipelago of desolate beaches, monuments and ruins. The library originally provided you with the option to scan through these panoramas and click through to nearby landmarks.

This not only moved you through the virtual space, but into a different version of the archipelago. You might set out for the conical monument on a nearby island, framed white against a summer-blue sky, only to arrive at its blackened remnants.

In its original form this work intricately combined these texts and images to create an eerie, cyclical world. But only two decades after its release, the formats it used have moved on–or gone extinct–and with them have vanished many former routes through the library. Even the ones remaining seem less reliable. It is easy to get stuck looping through the same locations, unable to break out, unable to reach landmarks you know to be close by.

And yet there is something darkly fitting in the way “Reagan Library” has unravelled. The fragments–the samples–we can still pull from it are themselves preoccupied with death, disintegration, entropy and memory. Its narrators find themselves stranded among and attempting to make sense of its ruined monuments. It is strangely appropriate that we should find ourselves in the same position in relation to this work, two decades on.

Traversing the library

“Reagan Library” is unexpectedly vast. You can be several hours into a session, have mapped out most of its locations, got an overall sense of where things sit in relation to one another, only to click through to an unfamiliar monument–or a familiar one in a new light–and face more broken text. You can pass through a location and never pass it again, or at least have enough time elapsed to forget you had ever passed it when you do eventually return.

It may be possible to fully map out, exhaust, the library in one session. More likely it will be something you revisit, crossing through many of the same places, yes, but each time also arriving at a different sense of its overall space.

One of my sessions predominantly cycled through worlds differentiated by blue and green text, whose narrators better remember who they were outside the library. Another session saw me returning to the worlds differentiated by black and red text, more ruinous, their narrators abstracted and amnesiac.

There are four world states to the library–black, blue, green, red–differentiated by changes in font and colour scheme in the text, and by the quality of light in the panoramas, but they all take place in the same archipelago. You will rarely remain in one world state for long, as the hyperlinks transport you across wide distances This can make exploring the library a pretty disorienting experience. It resists mapping, forces you instead to reconstruct from incomplete samples.

Blue world–Emily Saint Cloud

Emily Saint Cloud is the narrator of the blue world state. She is possibly dead. Her text fragments recount episodes from her life: dumping a time capsule–a car full of stuff–into a vacant lot in Sarasota, films she produced, her tendency to dream in landscapes and her childhood desire to be a dragonfly.

Emily seems aware she is dead or dying, that she now inhabits a space of her own making:

This world has a basic circularity. Everything changes, everything comes around. Movement is possible. The camera can be in motion if you like… This is the world I made, a garden of remembering. Emily is good at remembering

Green world–unnamed

The unnamed narrator of the green world state once worked as a comic. They have suffered an injury, severe burns–possibly due to a plane crash–and are now stranded somewhere between consciousness and unconsciousness.

Center, okay, center. The center is the place with the pillars, can’t say as I’m thrilled with the color scheme but it seems there’s only myself to blame. I can see a few things, though it’s generally hazy, and actually that suits me. I’ve always been a bit of the not-quite. Now I’m even more.

Interestingly, despite the extent of their injuries, the narrator is able to converse with their doctor. An explanatory note in another text fragment suggests that “virtual reality has been used as an effective therapy for burn patients.”

But the nature of this world remains unclear: while some structures are unfamiliar, others have a direct analogue in the narrator’s former life. Encountering the white cone, a strange humming prop from an old film, they note they are “not surprised to find it here.”

Black world–the man in the library

The texts in the previous world states take an autobiographical tone: whatever their present situation, their narrators have at least some idea of their previous lives. In this case however, the narrator wakes up with no memory, only the understanding that he is here as punishment:

I awoke one inky midnight in the library. It was not what I expected, but here I was, poured out on the blank sands, my conviction duly registered, sentence indefinite… The facts I don’t recall, so I am condemned to repeat.

An explanatory note in another text fragment names him as “the man in the library.” His narration is preoccupied with crimes and punishments. Fittingly, the archipelago takes on a distinctly sinister, carceral atmosphere, the structures crumbling into ruin, others on fire.

Similar to the others, though, the man is a disembodied presence in the library. In one location, looking out from inside a burning building, he remarks “there is no pain, for I have no body to suffer, but in the mind likewise nothing stirs.”

Red world–unnamed

The voice of the red world state acts as a guide to the library. Its text fragments consist of numbered lists that explain how to get around (“let’s move the camera”), what to look out for (“count the dots”), how to interpret the monuments, the narratives, the nature of this world (“the man in the library has been condemned”).

Initially, these lists offer a way through the disorienting texts and images. Like plaques in a museum. They definitively set out the rules of the library, delineate its inhabitants, ask you to continue reading and assure you that there will be a definitive ending to this work, that you will know it when you reach it.

I think is telling, though, that unlike museum labels these notes are not located next to the other text fragments as footnotes or marginalia, but instead inhabit their own discrete world state, and an ominous one at that, with red sea, red skies, and long sunset shadows. I get the sense this voice is just as stranded in this world as any of the others. Its lists may be more archaeological than truly authoritative.

Erosion and reconstruction

As you cycle through the library, revisiting locations, as texts in the black, blue and green worlds gradually cohere, those in the red world instead fall to pieces:

Belly to belly, earth and sky beget horizon, axis of each.

Study the appearance of all things, for things are not as they appear.

Much depends on the color of the sky.

Worlds were made so the light could speak to us.

This is not the end of the world.

Dave Youssef, writing about the depiction of monumental space in this work, notes these red world texts serve to position the narrative within a historicist framework of “what really happened.” He reads their steady breakdown as a commentary on the way the preservation and sense-making attached to monuments serves to erode the actual historical contexts in which they were situated:

By virtue of the monument’s projection into a “world beyond” which may not maintain or understand it, allowing it to fall into ruin, it will come to stand in for a historical era from whose everyday practice it remained essentially disconnected.

It can be jolting to return to red world texts when the narratives have started making sense elsewhere. If the library is essentially a collection of disordered and eroded memories, it is as though the narratives we have been so far able to reconstruct are now confronted by their residues, their remainders, the bits we were unable to fit anywhere and keep it coherent, pooling here instead.

Repeatedly visiting these texts gradually brings them into focus. We could see this as approaching their original form, of approaching their underlying truth. Alternately we could see this as an act of reconstruction, of separating signals from noise but ultimately getting no closer to any underlying truth than in the initial, disordered versions.

Youssef, once again, suggests that this interpretive act is complicit in the erosion of the actual historical context that the library or archive intends to preserve:

An archive not only disintegrates and loses its coherence from a lack of individuals to maintain it but is also subject to inadequacies in its structural integrity that result from its use and constant re-interpretation by outside viewers.

Is our guide to this space, the one that tells us Emily Saint Cloud is dead, that virtual reality is an effective treatment for burn patients, that the man in the library has been condemned, at all reliable? It assures its audience, “you’ll know when you’re done,” but given its own steady erosion over the course of any session, this is possibly not something it can truly deliver. Even if not possible within the code itself, we can imagine these these texts may be recombined in wholly different ways, to wholly different ends.

Stranded in the library

From the perspective of its narrators, the library is alternately a garden of remembering, a last-resort medical intervention, a prison and/or a broken landscape that has long forgotten its own history. Uniting all of them is an awareness that not only are they somehow now inhabiting this library, they will also never be able to leave the library.

“Reagan Library” is limbo, a vegetative state, eternal condemnation, lost history. I find it profoundly claustrophobic. I imagine it as analogous to the way dementia or irrecoverable memory loss may feel to experience, a state of deterioration from which there is no return, no pathway back to full lucidity, and worse, the awareness that this is the case.

That said, there is something resonant (if bleak) in accepting this. The best that the narrators stranded in the library can hope for is to reconstruct things just enough to continue on in its half-light world. But this holds true for us, out here too, surrounded by the wreckage and failed monuments of our own histories.

Take him to the theatre who loves to dream. I still lose my way between falling and flying.

Probability of closure now 14% and falling.

See also

References

- Moulthrop, Stuart, “Reagan Library,” in Electronic Literature Collection 1, eds. N. Katherine Hayles, Nick Montfort, Scott Rettberg, Stephanie Strickland (College Park: Electronic Literature Organisation, 2006), online

- Youssef, David, “Electronic Ruins: Virtual Landscapes Out of History,” in Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary, eds. N. Katherine Hayles, Christopher Mott, Jacob Burch, 2008, online

Endmatter

Tags: @archival @completed @cybertexts @virtual-spaces

Return to: Ormulum