My Trade

Created: 2023-08-05 (12:00:00) — Modified: 2025-06-27 (20:12:39)Status: completed

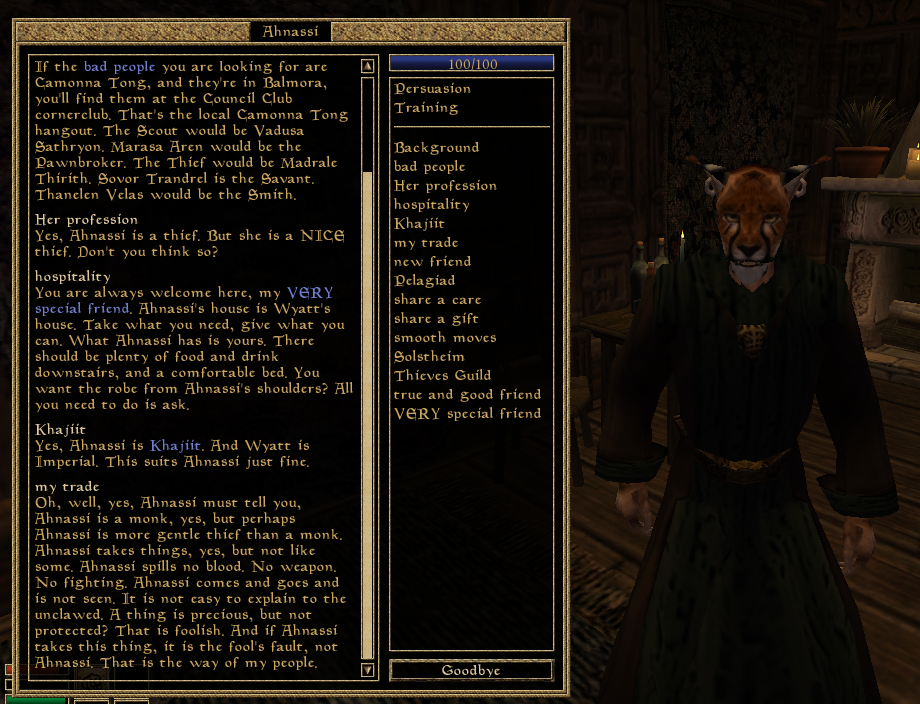

When you open a conversation in The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, it looks like this:

A window dominated by one big text log, and a sidebar with a list of commands (admire, bribe, taunt, intimidate) and topics (background, little secret, my trade, rumours). Clicking one of these topics appends a text passage into the text log on the left, so that as you click through them you develop an increasingly long conversation history you can refer back to. Selecting some topics will cause more to appear in the sidebar, or alternatively, lead the other character to abruptly break off conversation with you. Based on how well disposed the other character is towards you, their responses will change too. If you’re on good terms they’ll answer most things pretty positively. If they’re neutral they’ll make small talk but evade sensitive topics. If they dislike you, they’ll tell you to go away if they don’t simply try to kill you first.

I love this system. For a game known for its unusual lore and surprising and beautiful art direction, the dialog system is one of the more secretly fascinating bits of Morrowind. This is not to say it’s an entirely effective or realistic way of conveying dialog. Lots of characters share the same responses to topics, meaning you’ll elicit identical responses from wildly different characters. When you encounter someone under the influence of the game’s evil, immortal god Dagoth Ur, most of their dialog will be unhinged and antagonistic, like:

“Lord Dagoth has sent the blight to destroy the foreigners, and to chasten those Dunmer who bend to foreign will. Those who oppose Lord Dagoth shall wither and die, while those who join Lord Dagoth shall be healed and strengthened, filled with the power and glory of Red Mountain, and inspired by the dreams of Dagoth Ur.”

Or:

“You will die, false one. Your flesh will feed us all.”

And so on. But then, it’s not too difficult to divert them and elicit the same kind of polite small talk you’d get from the other commoners who make up the population, for instance when asking them about an island up north:

“A terrible place, I’ve heard. There’s a boat from Khuul, if you have any reason to go.”

Because none of this is voice acted, you’ll find the characters often don’t so much respond conversationally. Instead they’ll deliver short monologues on anything ranging from that island to the north, to their professions, to the services available in town. In this vein, I find asking characters about their trade to be a particular source of unintentionally funny dialog. You’ll walk up to some shady looking person on the street and ask them their trade, and get an open admission that they kill people for a living:

“I’m an assassin. Killing is my profession. I am discrete, efficient, and reliable. In Morrowind, the assassin’s trade is an ancient and honorable profession, restricted by a rigid code of conduct, and operating strictly within the law. Because I am discreet, I prefer short blades for swift, close-and personal work, while the marksman weapons like throwing stars and throwing knives are more suitable for stealth and surprise. I charge fair prices to train apprentices in the assassin’s skills.”

Or they’ll give you an eloquent account of their peasant lives:

“I am a pauper, one of the humble smallfolk. I make my way in the world as best I can, laboring in the fields, kitchens, and factories of lords and merchants. When times are good, I live well enough by my own work. When times are hard, I must hope for the charity of the nobles and wealthy merchants.”

The effect feels reminiscent of a theatre production, as though the actor is stepping outside the action to deliver a soliloquy. The writers could have just had their characters say “I’m a pauper,” or stuck in some muddled, faux-realistic dialog. I’m grateful for what we got instead. Characters’ responses to other topics read like encyclopedia entries or extracts out of guidebooks, enumerating all the people and places of interest in the region, to a level that exceeds simple recall:

“All six Redoran councilors, Brara Morvayn, Hlaren Ramoran, Athyn Sarethi, Garisa Llethri, Miner Arobar, and Bolvyn Venim, live in the Manor District. Edwinna Elbert is Mages Guild steward, Percius Mercius is Fighters Guild steward. Old Methal Seran is an eminent Temple priest and scholar. Raesa Pullia is commandant of Fort Buckmoth, but Imsin the Dreamer is the chapter steward. The Redoran Hean is priest of the Imperial cult. Find Goren Andarys, guild steward of the Morag Tong, in the Manor District.”

So the dialog in Morrowind is not in the service of any kind of realism. Compare it to the voice acting and uncanny zooms on characters’ faces in the later games. Dialog in Morrowind is more like looking things up in an encyclopedia. I appreciate the artifice, the lack of realism. Part of this is probably nostalgia for the nineties and early two-thousands games where these systems had their heyday, but also because are also interesting questions what kinds of affordances we get from these interfaces, what they make possible, what possibilities they close off, beyond just trying to be naturalistic.

The few modern games I’ve placed, if they offer branching dialog at all, usually limit it to one or two options. There’ll be a couple specific things you can raise with each character you encounter, usually with voiced responses. Because the game can’t just print reams of text in a window, the writing has to be more concise. It has to try approach something like the way people actually speak. (And even moreso when someone actually has to voice those lines, and when you the player have to then listen to someone voicing those lines.) Not that this turns out to be any more accurate a reflection on how people actually speak, anyway:

“Never been to Whiterun before? The Jarl’s palace is something to see. Dragonsreach they call it. Big old dragon skull hanging on the wall.”

If videogames are going to be peculiarly incapable of reflecting the way people actually speak, why foreclose on all the sprawling fun of old roleplaying games like Morrowind? I want long, weird monologues to come back. I want, when a character is prompted about local rumours or gossip, to respond with a rambling passage of text no person would actually have the patience to sit through in reality. If novelists can get away with sentences that run for pages and pages, then there is no reason for games to limit themselves to this faux-naturalistic two-to-three line dialog.

More generally, I want to see more novel dialog systems, more experimentation with the form. What about something that sprawls out endlessly, a voice that you can become thoroughly lost in, that shifts irreversibly the moment you try to interject. Bring back encylopedic topic lists and text-parsing and that system where you can show an item to someone to elicit a unique response! There are, moreover, whole realms of potential in other interactive fiction. What would a dialog system look like that was modelled on Reagan Library’s cycling text extracts that gradually cohere or disintegrate, or on Uncle Roger’s lexia linked together by associative keywords?

See also

Endmatter

Tags: @completed @cybertexts @games @virtual-spaces

Return to: Ormulum